Argument

The term “traffic” in the Prologue’s “two hours’ traffic of our stage” has an overlooked significance, conveying “trade of an objectionable nature” and anticipating Romeo’s use of a two-part cash bribe to reach Juliet’s bedroom. [1200 words]

Did you know Romeo spends but one night with Juliet? Did you know he pays for it?

It’s the world’s most famous love story, and not for no reason. The children of two enemy families, Romeo and Juliet meet, fall instantly in love, and ultimately take their lives for one another.

What possible basis could there be for questioning the sincerity of their affection? Here’s one: Romeo’s use of a two-part cash bribe to reach Juliet’s bedroom.

As you’ll see below, there’s nothing equivocal about what Romeo does, or why. But a conspiracy of silence surrounds the event, critics simply never mentioning the self-evidently dubious, gold-for-girl commercial transaction at the play’s center.

The play actually opens with a suggestion that it’s going to feature a sinister form of trade. In particular, when the Prologue speaks of the “two hours’ traffic of our stage,” the term traffic conveys “trade of an illegal, immoral, or otherwise objectionable nature” (Oxford English Dictionary 2). As such, it suggests the characters may use finances in illicit ways.

So, are there any questionable business dealings in the action that follows? Yes, there are two.

There’s Romeo using gold to buy “drugs” in Act 5.

And there’s Romeo using gold to buy sex in Act 2.

It’s Act 2, Scene 3, and the day after the Capulet party. Mercutio and Benvolio run into Romeo on the street. Immediately, they wonder what he’s up to. The night before, he’d abandoned their company to pursue a girl, leaping a wall onto private property. Presently, he stands there in his dancing clothes—a sure sign he never went home. Further, he’s been extremely reclusive in recent weeks, avoiding both people and daylight. Why now is he out in public?

When the Nurse arrives, asking for Romeo’s “confidence”—that is, his participation in the “confiding of private or secret matters” (OED 6)—the friends have their answer. “She will indite him to some supper,” says Benvolio, suggesting they’re up to something illicit. Mercutio, suspecting outright procurement, cries,

A bawd, a bawd, a bawd! Soho!

A “bawd” is a paid procuress, “soho” a hunting call used to announce a discovery.

According to the insinuation, Romeo is going to meet with the old woman, arrange a surreptitious, that-same-night sexual encounter, and compensate her financially for her help.

It’s outrageous! The Capulet caretaker—a procuress? Pimping out the girl in her care? Romeo—a john? Trading cash for sex? Trafficking—at the heart of the world’s most famous story of “love”?

Outrageous and—exactly what happens next, Romeo proceeding less than fifty lines later to meet with the old widow, tell her how she can help him reach Juliet’s bedroom, and then remunerate her—and not once but twice.

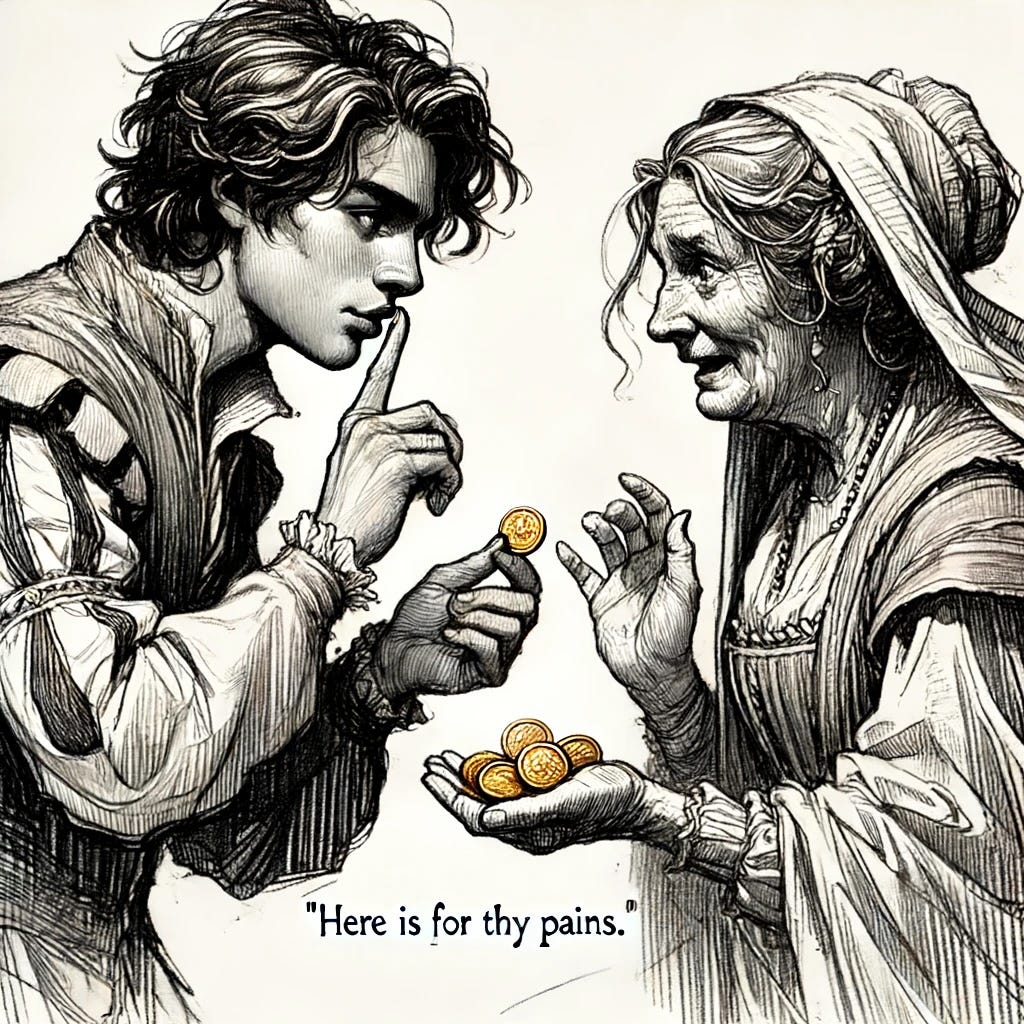

First, he tells her to tell Juliet to make up an excuse to get out of the house. “Bid [Juliet] devise some means to come to shrift this afternoon,” he says. That is, tell her to tell her parents she’s off to confession. Then, he reaches out his hand:

ROMEO Here is for thy pains.

NURSE No, truly, sir, not a penny.

ROMEO Go to, I say you shall.

NURSE This afternoon, sir, well, she shall be there.

Romeo’s “Here” suggests he’s showing the Nurse the coins. His “Go to” suggests something more aggressive still—that he’s placing them right in her hand.

Romeo himself knows the tempting or corrupting power of gold. Later on, he’ll call it a “poison to men’s souls.” Yet here, he does not hesitate to use it to entice the deep-into-her-dotage Capulet caregiver.

Another ten lines later, following another series of instructions, Romeo promises still more money—on the condition she keeps quiet about what they’re up to. “Farewell,” he says,

Be trusty, and I’ll quit thy pains.

Be trusty: tell nothing to nobody. And I’ll quit thy pains: and I’ll reward you again. (To quit means to ‘‘pay or repay a person for a kindness or favour’’ (OED 3)).

Put differently: after I’ve successfully made my late-night visit, I’ll give you another handful of 24k coins. You wouldn’t expect it all up front, would you? Let’s talk again post-coitally.

Romeo’s so desperate for sex he’d pay for it, insinuates Mercutio one moment, preposterously. The next, Romeo’s slipping gold to a go-between.

One moment, Mercutio says Romeo’s up to something shady. The next, he’s planning his climb in “the secret night,” an index finger on his lips.

And do you know? I’m not sure what the bigger scandal is. The event itself. The Montague taking advantage of the unscrupulousness and avariciousness of a semi-senile old woman to set up a surreptitious carnal encounter.

With the thirteen-year-old he met at the previous night’s masque.

Or the near-total silence about the event in the secondary literature. Where it’s as if it just. never. happened.

Either way: the Nurse is a bawd indeed. A dealer-in-girls. Young girls. Girls so young they still sleep with you at night (as Juliet still sleeps with her live-in custodian).

And Romeo? A client. A user. A twice-paying john.

And Juliet? Well, as she herself says, as her wedding night approaches, in one of the most unwitting remarks in the play, she’s “sold, / Not yet enjoyed.” Indeed.

Thus, with its pronouncements about the “death” of the lovers and the “bury[ing]” of “their parents’ strife,” the Chorus anticipates such major events as the lovers’ suicides and the cessation of the feud. With its use of “traffic,” the Chorus looks ahead to the titular boy’s pecuniary pact with the Capulet caretaker-turned-procuress, where, clandestinely, apart from his friends, his pockets filled with gold, Romeo hire purchases his way into the bedchamber of the barely-out-of-childhood girl in her charge.

He traffics in drugs. He traffics in sex. And to this day his name remains universally synonymous with model romantic lover.

As seen from Act 1 Scene 3, the Nurse has a bawdy and earthy view of sex. She's not romantic at all. Quoting her late husband talking about Juliet:

'Yea,' quoth he, 'dost thou fall upon thy face?

Thou wilt fall backward when thou hast more wit;

It would be interesting to compare what you've written to other plays. Shakespeare frequently compares different types of relationships to commerce -- the Merchant of Venice is the most obvious example.

My take on the play: Romeo had infatuation on Juliet, who was ‘forbidden fruit’ being from enemy family. This lifted his lust to wanting sex at all cost. Bribed her Caretaker to get access to her room but wasn’t paying Nurse as Madam of Juliet. Sex was so good and tender that Romeo got in love suddenly. This newly found love between two teenagers ended in tragedy …