Romeo’s “Mischief”

Can a single word undo the romantic understanding of Romeo & Juliet? This one can

Argument

In Act 5 of Romeo & Juliet, Romeo attributes his suicide to Mischief personified. In Shakespeare’s day, mischief didn’t mean “petty annoyance.” It meant “evildoing, wickedness.” Currently, critical editions, including the Oxford, Cambridge and Arden, fail to define mischief for readers—a blatant instance of editorial bias.

In life, [love] doth much mischief, sometimes like a Siren, sometimes like a Fury.

—Francis Bacon

At the beginning of Act 5 of Romeo & Juliet, Balthazar tells Romeo that he has seen Juliet “laid low in her kindred’s vault.” Immediately, Romeo decides to go to the tomb and kill himself by her side. As he decides on the “means” by which he’ll take his life, he says something extremely revealing. “Well, Juliet, I will lie with thee tonight,” he says,

Let’s see for means. O Mischief, thou art swift

To enter in the thoughts of desperate men.

I do remember an apothecary

(And hereabouts he dwells) which late I noted…

Romeo proceeds to describe the Apothecary’s shop, and then to go and make his purchase. In fact, he buys the poison less than twenty lines after the words above.

But my interest here isn’t the idea itself but its source, namely, Mischief personified. In my view, Romeo’s apostrophe to Mischief is one the most significant utterances in the play. What’s so important about it? Simple: mischief didn’t mean in Shakespeare’s time what it means now—not even close.

Today, mischief means “vexatious or annoying action or behaviour,” a meaning it’s had since about the end of the 18th century, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (or OED).

But at the time of the play’s writing, mischief was synonymous with evil. When used to refer to something bad that happened to you, the term could mean “misfortune, bad luck” (OED 1). But in a more active sense, mischief meant “harm, injury, or evil done to or suffered by a person” (OED 2) or outright “evildoing, wickedness” (OED 5).

Shakespeare often uses the term in this way. For example, in Venus & Adonis, the goddess tells the boy that failing to reproduce himself would constitute “A mischief worse than… theirs whose desperate hands themselves do slay, / Or butcher sire that reaves his son of life”—that is, the greatest possible crime, worse than suicide or filicide.

Similarly, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Demetrius threatens Helena, “if thou follow me, do not believe / But I shall do thee mischief in the wood.” Helena responds that she would gladly “die” at Demetrius’s hands, suggesting she understands him to be threatening either murder or, as the figurative sense of “die” conveys, rape. As one editor notes, “Helena seems to suggest she would find ecstasy even in being raped by Demetrius” (Chaudhuri 165n).

Incidentally, in his gloss on mischief, this same editor (Chaudhuri) rightly defines it as “serious harm or injury,” points out that it had “a much stronger sense than [it does] today” and compares the phrase “hellish mischief” from Henry VI: Part 1. Of course, this is both correct and helpful. But as we’ll see below, editors of Romeo & Juliet all conspicuously fail to do the same. The question’s why.

In Shakespeare’s principal source, Arthur Brooke’s Romeus & Juliet (1562), Brooke uses mischief in the same way on the very first page of the text. In particular, in his “Address to the Reader,” where he describes the moral purpose of the work, Brooke says that just as “the good man’s example biddeth men to be good,” so “the evil man’s mischief warneth men not to be evil.” The “evil man’s mischief”—today, we would never see “mischief” and “evil” together in the same line, or only in a playful or ironic sense. But in the sixteenth century, such phrasing was normative.

Therefore, with little if any doubt, when Romeo apostrophizes Mischief embodied, he doesn’t address Annoyance embodied. He addresses Evildoing embodied. As such, he characterizes his suicide itself in about the most negative terms possible—as an act of unadulterated wickedness.

An editorial oversight—or omission?

But here’s where things get more interesting still, for editors of critical editions of Romeo & Juliet don’t seem to want you to comprehend Romeo’s—Shakespeare’s—meaning. Why would I say this? Because in most if not all critical editions available today, editors neglect to define the term for readers.

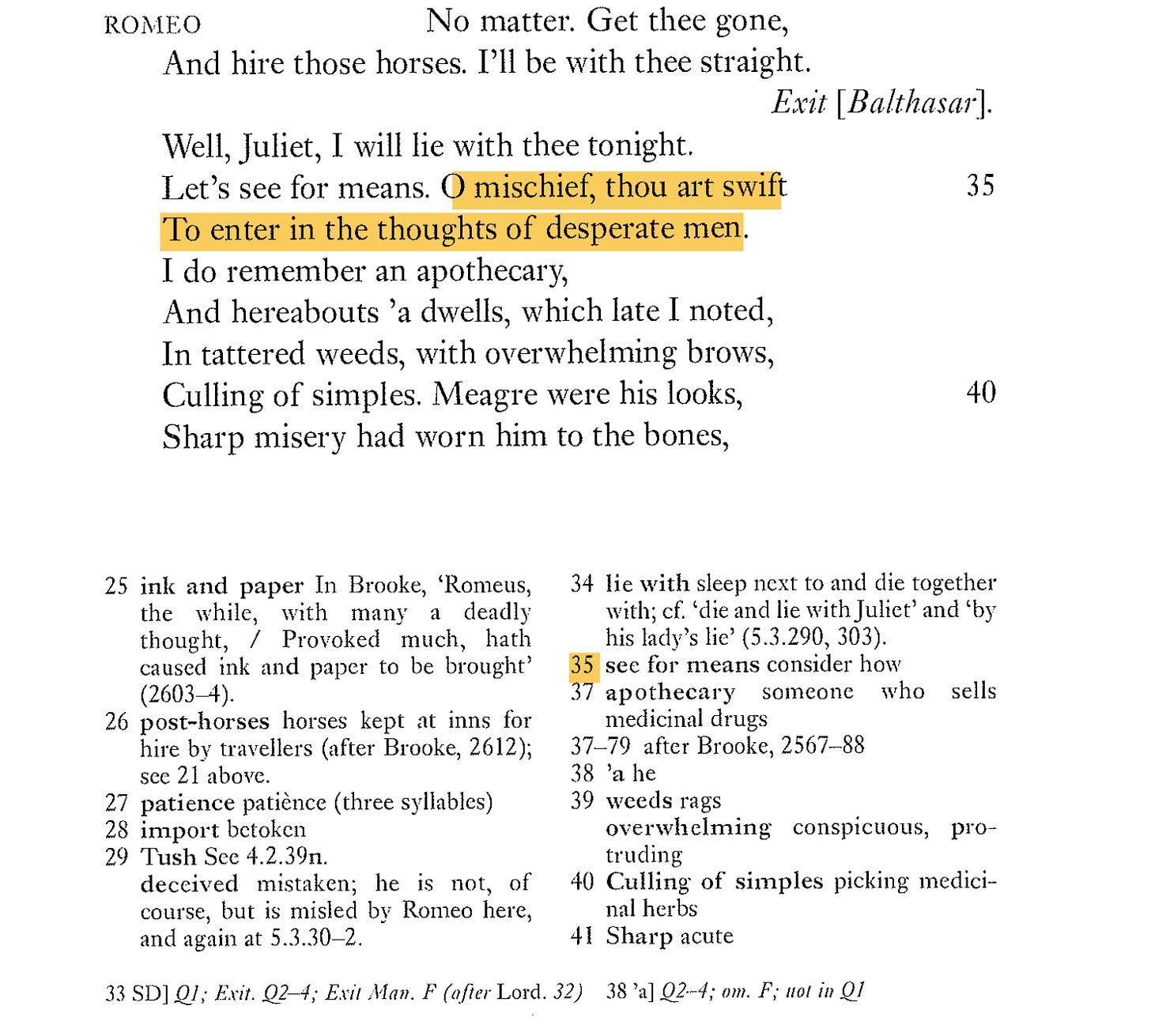

For example, here’s the Oxford edition, edited by Jill Levenson:

In the note for line 35, you can see that Levenson defines “see for,” a phrase that isn’t particularly ambiguous. Does anyone read “Let’s see for means” and not know what Romeo’s saying? But like other editors, Levenson apparently aims to provide readers with more rather than fewer glosses.

Yet conspicuously absent is a definition for the object of Romeo’s apostrophe and source for what is by far the most decisive action in the play.

Did Levenson not look up mischief’s meaning? That’s possible, but unlikely. If you glance at the other glosses on the page above, you’ll see “OED” multiple times—and for good reason. When editing such a volume, scholars don’t look up the odd word. They live in the OED. As such, it’s hard not to see the omission as deliberate.

And in this, the Oxford is representative. The Cambridge, the Arden, the Norton—all of the most recent and prestigious and comprehensive critical editions fail to define this term. I know this may be hard to believe, so here’s another screen-shot, this one of the Arden:

As you can see, exact same situation.

What can explain this? Is the problem that editors aren’t seeing the definition? Or is the problem precisely that they are? In this one instance, are editors neglecting to open up the OED? Or are they finding “evildoing, wickedness,” drawing back in modern-minded, academic-minded horror and going whoa, not sharing that with my readers?

Wouldn’t want to, you know, give them the right idea.

At the risk of sounding conspiratorial, I’m not sure this editorial lacuna, universal in nature, is accidental. Rather, I think editors are reading the Elizabethan sense of mischief, perceiving the end of the romantic conception of the play, and knowingly leaving a gap in the notes.

And hoping no one ever notices.

Mischief—the character

But there’s something else I haven’t yet mentioned, and it may be the most interesting and important point of all.

In sixteenth century drama, mischief wasn’t just a provocative concept. He was a character! And a well-known one, with a very specific role. Can you guess what it was?

Enticement to suicide. Soul-damning suicide.

In particular, Mischief was one of the personified vices in morality plays, a genre that flourished in England and across Western Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries, and one that had a profound influence on Elizabethan drama.

For example, in Mankind (1470), Mischief does everything he can to entice the protagonist to take his own life. Near the end, Mankind despairs, considering himself corrupt and irredeemable. “A rope, a rope, a rope!” he cries, “I am not worthy.” Mischief responds,

Anon, anon, anon! I have it here ready,

With a tree also that I have get.

In other words, Move as quickly as possible! Here’s everything you need, including a rope and a tree-branch. Instantly, two of Mischief’s companions are setting up the makeshift gallows. They even demonstrate what to do, one holding the branch while the other puts his head in the noose.

Hilariously, the first gets distracted and accidentally strangles the second. “Alas, my throat!” the latter cries, “Alas, my weasand!” (A weasand is a “wind-pipe, or throat generally”).

Mankind is about to hang himself—when Mercy arrives with a rod, beating the vice figures and telling Mankind it’s not too late to repent. “Yet for my love ope thy lips and say ‘Miserere mei, Deus!’” Mercy tells Mankind. He further instructs him to “be repentant,” saying “now is the day of salvation.” As a result of the last-minute intervention, Mankind saves his life and soul.

Similarly, in John Skelton’s Magnificence (1516), Mischief and Despair work together to tempt the protagonist to take his life. “Thou art not the first himself hath slain,” Mischief tells Magnificence, handing him both a rope and a knife. Despair adds, “Yea, have done at once without delay.” Here too, the man is about to commit suicide—when Good Hope arrives, preventing the man from condemning his soul to eternal pain.

In Shakespeare’s play, Romeo clearly addresses this same figure. According to his own terms, Mischief’s “swift,” acting as quickly as possible—and urging his victims to do the same. In the same line, Romeo calls himself “desperate,” referencing both a damnable state of mind and Mischief’s companion in the play just mentioned. Finally, here too Mischief provides Romeo with the actual means to kill himself.

Do you see? It’s an allusion! And one of the most important and consequential in the entire play.

For modern readers, the reference is bound to seem obscure and pass without notice. But for Shakespeare’s audience, the opposite would have been true. Most if not all would have been familiar with Mischief and comparable Vice figures, and known exactly what they symbolized. The reference would have told them all they needed to know.

The point can’t be overstressed: a suicidal individual expressing allegiance to a personification of vice: in Shakespeare’s day, this idea wasn’t opaque or uncommon. It was conventional.

The main difference between Romeo and these other everyman figures? At the end of Shakespeare’s play, there’s no Mercy or Hope to step in to save him.

Therefore, Mischief doesn’t just deserve a note. It deserves an extended note. For example, it deserves to be in the “Supplementary notes” of the Cambridge edition, with other terms or references requiring more in-depth discussion. But I don’t think I’m telling editors anything they don’t already know.

In theory, editing is a dispassionate effort in which a scholar does everything he or she can to help the reader grasp the text as fully as possible. In practice, it works a bit differently, editors sometimes working to protect their own ideas—and egos.

Sometimes, silence is the best corroboration.

Conclusion

In effect, Romeo, like Magnificence, meets Despair and Mischief—and acts precisely in accordance with their evil-minded exhortations, capitulating to the worst and lowest of his own tendencies.

Were this a morality play, there would be no doubt about his fate.

And guess what? It is a morality play. A Renaissance morality play, where the protagonist’s story has the same eschatological significance, but where the forces of good and evil are reinternalized, fighting it out on the battlefield of the human breast.

At least, that’s one of my main contentions.

One I can’t wait to share.

Hello John. I am very much enjoying your de-romanticising of R+J.

This issue of Romeo's suicide, his desperation - whether motivated by impetuous youth or something else - giving rise to eternal damnation, reflects interestingly on the later tragedies,, especially King Lear. Some critics view Lear as reflecting Shakespeare at the end of his tether, depressed, played out. Yet your reading of R+J suggests Shakespeare possessed a dark view of the human situation, or at least of Elizabethan society, in the mid 1590s. Lear is bleaker overall. But when we consider the plays written around the time of R+J - Love's Labour's Lost, Midsummer Night's Dream, Richard II - we can see Shakespeare pushing the envelope in comedy, history and tragedy ... and that these genres bleed into each other in all four plays. A dark streak washes through them all, but varying to greater or lesser degrees.

Your observations suggest that R+J is the key to unpicking the overlaps and identifying their psychological and moral complexities, because it is the play the is most misread out of these four. I'm looking forward to further insights from you.

PS. Your interactions with Stanley Wells are hilarious - in a straight-faced scholarly way.

What a fantastic challenge to the status quo approach to Romeo and Juliet. You back up your thesis well, and I'd love to see a response/debate. Unfortunately, mischief appears to be in the air!